Amber Li

The Transformative Power of ‘Womb Magic’: Eileen Agar at the

Whitechapel

Eileen Agar, 1927.

( NPG 5881)

(© Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

Upon entering Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, the Whitechapel

Gallery’s current large-scale retrospective exhibition, we are faced by three

large oil portraits. The central of these is a self-portrait, painted in 1927. As

both subject and artist, Eileen Agar (1899-1991) exudes self-assurance. The

work marks a pivotal moment in which she rejected the artistic conservatism of

her training at the Slade School of Fine Arts, and escaped her socially

restrictive, upper-class upbringing. In a narrative shared by women

Surrealists, Agar’s rebelliousness brought her into contact with Surrealism in

Paris. ‘Self-Portrait’ signals

a dramatic remaking of personal and artistic identity. Agar’s

propensity for self-renewal shaped her life. Her memoir, A Look at My Life (1988),

opens with the outlandish claim of having been born three times: first

physically, then as a painter, and finally emotionally upon meeting her

lifelong partner Joseph Bard (1892-1975). The fluctuations in her identity are

inseparable from her work’s mutability: in a private notebook, now in the Tate

Gallery Archive, she wrote that art must be ‘infinitely susceptible to new

shapes because no shape can be regarded as final, the artist is in a state of

perpetual self-transformation’. While ‘Self-Portrait’

provides a starting point for

the exhibition in terms of location and chronology, it does not have to be the

only starting point. As viewers free to wander, we may consider the exhibition not

through the linear narrative of Agar’s life and work but as a series of

rebirths. Multiple identities co-habit the gallery space, residing in

paintings, collages, drawings, Surrealist objects, photographs, and archival

ephemera. Perpetually, they form new interactions, sparking new meaning and

moments of dialogue to be discerned or overheard by the viewer.( NPG 5881)

(© Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

In our engagement with these works, we might take inspiration from Agar’s own love of play and the unconventional. She created her work by allowing her imagination to transform her external surroundings: ‘Outer eye and inner eye backward and forward, inside out and upside down, sideways, as a metaphysical aeroplane might go, no longer classical or romantic, medieval or gothic, but surreal, transcendent, a revelation of what is concealed in the hide-and-seek of life […]’ In ‘Collage Head’ (1937) and ‘Marine Collage’ (1939), Agar cut classical statues from book plates, creating silhouettes by preserving their outlines in her collages. She then reversed these frames to reveal fragmented images overleaf: incomplete statuary and caryatids loom ghostlike in the margins. Facilitating a sudden, unexpected glimpse through to what lies on the other side, the collages make material Agar’s desire for art to create ‘holes in the walls of reality’.

Drawing on this model of mobility, what if we, the spectators, were to travel not around the opening wall but through it? On the wall’s reverse hangs ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’ (1933-34). Painted three years after Agar’s return from Paris, it is markedly ambitious in scale and iconography. Measuring two metres across and a metre tall, the painting incorporates forms both abstract and figurative. A modernist take on a Pompeiian frieze, it is organised in four rectangular panels outlined by colourful wavy borders and painted stone putti. Dispersed throughout are natural forms, cogs, embryonic cell motifs, and ethnographic and classical objects, layered in complex, rhythmic patterns to create a collage-like appearance.

These patterns allude to the cyclical relationships of beginnings, returns, and reinventions. Circles in the work resemble eggs, cell life, or possibly the ouroboros, a snake ingesting its own tail which symbolises the infinite regenerative cycle of life and death. Snakes are a recurrent metaphor for Agar, who later called herself a ‘metaphysical serpent who regularly sloughs her skin to reveal a new one’. ‘Self-Portrait’ marks the start of Agar’s professional career. ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’, its metaphorical counterpoint on the reverse of the wall, builds an imaginative universe around the very theme of beginnings. Various stages of foetal development depicted throughout the work hint at Agar’s fascination with the womb. Her 1931 article for The Island, an arts periodical she financed, declared that ‘the intellectual and rational conception of life has given way to a more miraculous creative interpretation, and artistic and imaginative life is under the sway of womb-magic’. Invoking a fertile, feminine imagination to counter ‘hysterical militarism’, Agar’s ‘womb-magic’ emphasises the importance of irrationality and embryonic, indeterminate states to an art that challenges the social values leading to war.

Such gendered terminology also points to Agar’s keen perception of her own unusual position as a professional woman artist in the 1930s. The Surrealists championed the feminine imagination for its irrationality and its proximity to the unconscious world. In ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’, huge, disembodied lips float above an open horizon, reproducing Lee Miller’s lips in Man Ray’s ‘Observatory Time, The Lovers’ (1932-4). Painted after Miller left Man Ray, his work is haunted by a spectral female muse. Agar herself contended with her portrayal as a Surrealist muse by male contemporaries, an identity she subtly undermined in works across multiple mediums. In her monumental painting, ‘Muse of Construction’ (1939), she playfully upends gendered tropes by casting Picasso as her muse. In ‘Ladybird’ (1937), she embellishes a photograph of her nude, dancing body with gouache markings evocative of the Oceanic and West African masks she collected and associated with totemic power, transforming herself into a strange, supernatural being. Perhaps most humorously, she satirises her mother’s obsessive self-fashioning in ‘Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse’ (1936-48), an absurd concoction of beachcombed shells, fishbones salvaged from her dinnerplate, and plastic starfish of the sort used to decorate Christmas trees.

Photograph of Ceremonial

Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1936.

( Private Collection)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

![]()

( Private Collection)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

Photograph of Agar wearing Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1936.

( Private Collection)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

( Private Collection)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

‘Autobiography of an Embryo’ substitutes the desirable exterior of the female body for its unfamiliar interior: the womb as the repository of the original uncanny, and the progenitor not only of human life but of the whole universe. Agar referred to ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’ as a ‘celebration of Life, not only a single one, but Life in general on this particular and moving planet,’ a representation in painting of what might nowadays be termed an ecological worldview. Marine, avian, and plant life proliferate throughout as dreamlike creations which mushroom from human heads. For Agar, nature, human life, and artistic creation are all irrevocably intertwined. In an early manuscript for her memoir, she described her painting process as ‘something that germinates like a seed […] slowly putting out shoots’. Completing this trinity, Agar further expressed an interest in rebirthing therapy, which she described as the idea that ‘patients should and could remember their experiences in the womb […] human foetuses have gills for around twelve weeks, because in the evolution of our species we went through an amphibious stage’. What structures ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’ is a deeply harmonic sense of universal order, pivoting on points of beginning and rebirth. This universal order, however, is irrational to its core. Subverting man’s relation to society as cog to machine, in Agar’s painting, cogs are reclaimed by a Romantic vision of nature. A vermilion starfish drapes its limbs over one, while another is occupied by clownfish and coral branches. Cogs appear liquid, spokes turned to fronds swaying in an invisible current. Covered in organic life, they are rendered functionless in a typically Surrealist juxtaposition of the dreamlike and the mundane.

Agar was fascinated by science, yet her interest was rooted in its potential for mystery rather than investigative knowledge. She chose to paint an embryo precisely because she ‘didn’t know anything’ about it and thought such life processes ‘extraordinary’. For artist and viewer, an absence of information activates the imagination to fill in the gaps. Agar provides us with an open-ended mode of engaging with the world alternative to Enlightenment empiricism, allowing wonder to flourish in its place. In the same vein, mystery conditions her inclusion of ethnographic and classical artefacts in ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’. Kourai, Minoan snake goddesses, and totemic figures are juxtaposed without hierarchy or discrimination, the hodgepodge result of rummaging through all of human culture for ‘an idea of how human, mankind, gradually evolved’. The work’s miscellany of references is an indication in microcosm of the expansive scope of material with which Agar engaged across her wider oeuvre. Together, they amount to a kind of world mythology, to be archaeologically excavated from the painting’s layered imagery reminiscent of palimpsests or geological strata. Concluding her piece in The Island, Agar wrote: ‘only by reaching back to the deepest and simplest emotional source native to a particular life-form can a creative harmony be projected into the world’. In ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’, the collected object becomes a metonym for artistic imagination across space and time, and all natural and cultural history occurs synchronously and interrelatedly. Within the unfolding narrative of universal embryonic existence, Agar locates a personal ‘autobiography’ of the artist’s creative journey through her right palm, transferred into paint in the lower left of the work.

Quadriga, 1935.

( Courtesy of The Penrose Collection)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

However, as with all acts of excavation, Agar’s search for beginnings is subject to incompleteness of information and loss of memory. She used stencils to trace the black outlines of objects onto the canvas, like museum postcards which have had their subject of interest removed. This is a technique she returned to throughout the 1930s in both Quadriga (1935), her contribution to the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition, and in her collages where processes of extraction are literalised through the act of cutting. The negative area of the stencil gives way to organic scenes beneath, semi-abstract in their fluidity. A pair of clownfish bubble liquidly across a profile, and a statue floats atop a blue-green background suggesting sea vegetation. In these examples, Agar punctures the skin of reality and gives the viewer a window onto another world. Elsewhere in the work, hybrid creatures recall the Surrealist exquisite corpse: a classical stone figure with an outsized, detached arm in the fourth panel dons a snake like a ceremonial headdress. Such incongruities recall a short story Leon Underwood (1890-1975) wrote for The Island, entitled ‘Lines Written in Mexico’. In it, he encounters a fallen Mayan god who laments the botched reconstruction of his world by modern archaeologists.

In ‘Autobiography of Embryo’, Agar exploits absence of information as a springing point for a vibrantly surreal imagination. Her championing of the unknowable extends to her own identity: in a notebook she once wrote, ‘if I knew myself, I’d run away’. Through artistic and personal rebirths staged at various points in her life, she resisted orderliness and categorisation. For Agar, beginnings are filled with indeterminacy, openness, and potential. The amorphous embryo could yet become anything. It is for us, as viewers, to imagine what that might be.

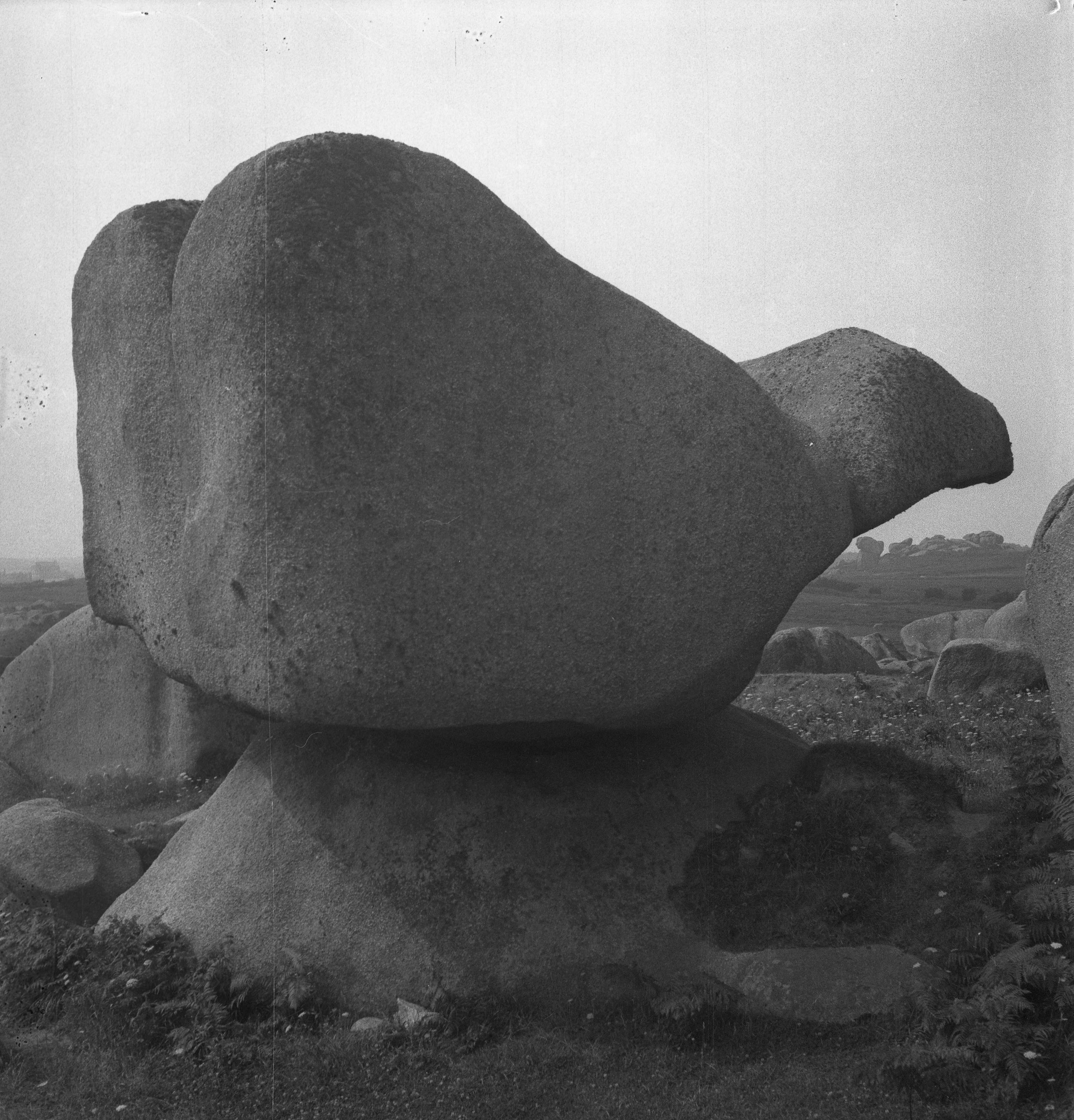

Left:

Photograph

of ‘Bum and thumb rock’ in Ploumanac’h, 1936.

( © Tate Images)

Right: Rock 3, 1985.

( Courtesy of Redfern Gallery, London.)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)

( © Tate Images)

Right: Rock 3, 1985.

( Courtesy of Redfern Gallery, London.)

(©Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images)