Dr Olivia Vane

Post-Covid Curation

As lockdown closed the doors of museums and galleries, attention has shifted to ways of ‘accessing’ the museum digitally. Before the lockdown took effect, I had plans to visit the excellent Van Eyck exhibition in Ghent. While I never made it to Ghent, anyone with an internet connection can now see it online as a ‘360° virtual tour’. But beyond reaching to recreate the experience of going around a gallery through a web interface, I hope this is also a moment for institutions to offer new ways of interacting with and presenting collections in digital that go beyond what is even possible with the physical items.

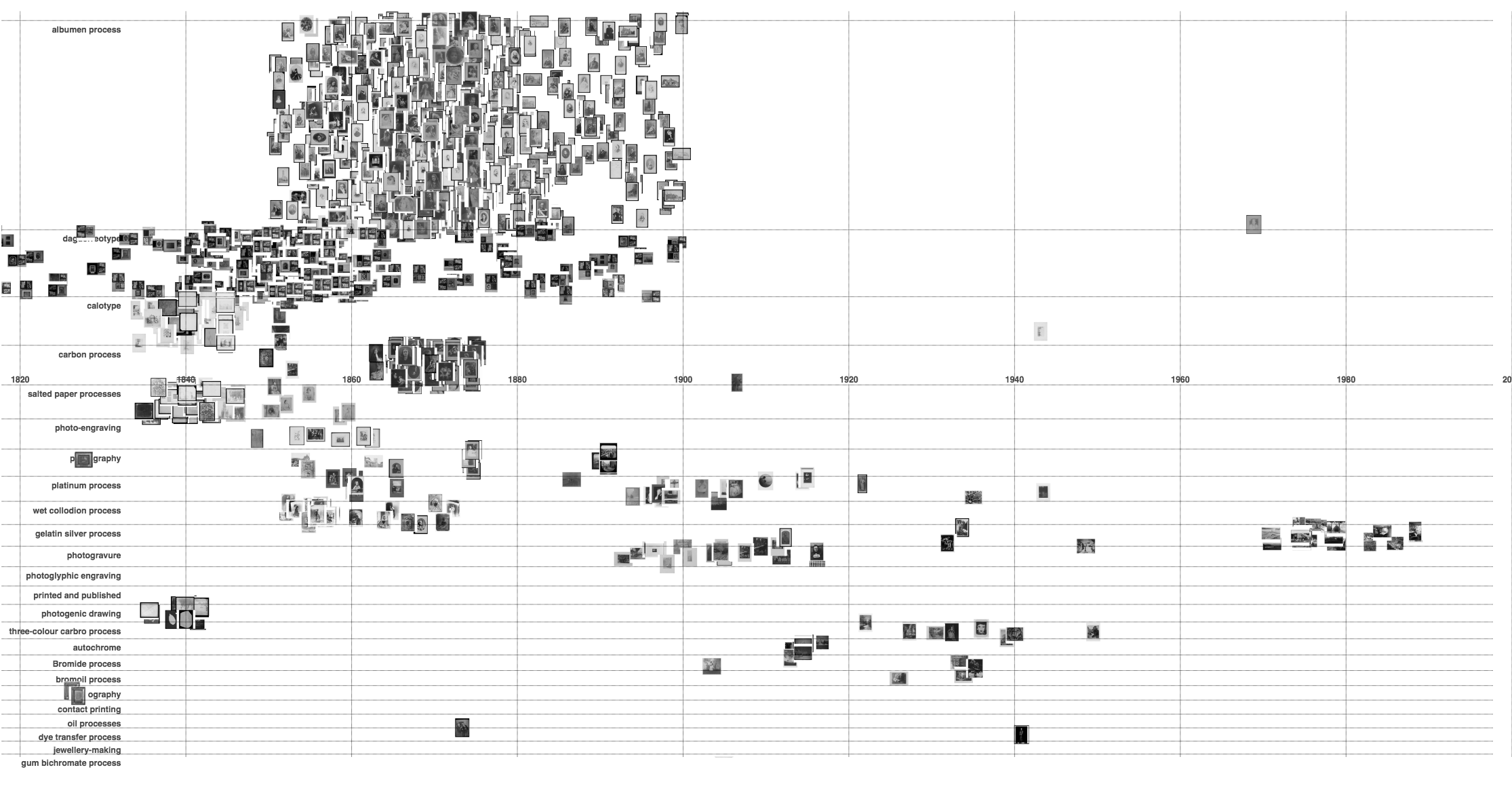

Olivia Vane. 2018. Visualisation of the Royal Photographic Society collection at the V&A Museum. Collection items organised horizontally by time and vertically by photographic technique.

Film director Wes Anderson, when co-curating an exhibition at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, was described as driving the curators mad with his strange requests, like a list of all the green objects in the museum (something their cataloguing system was not designed for). But once a collection is digitised, we can do this.

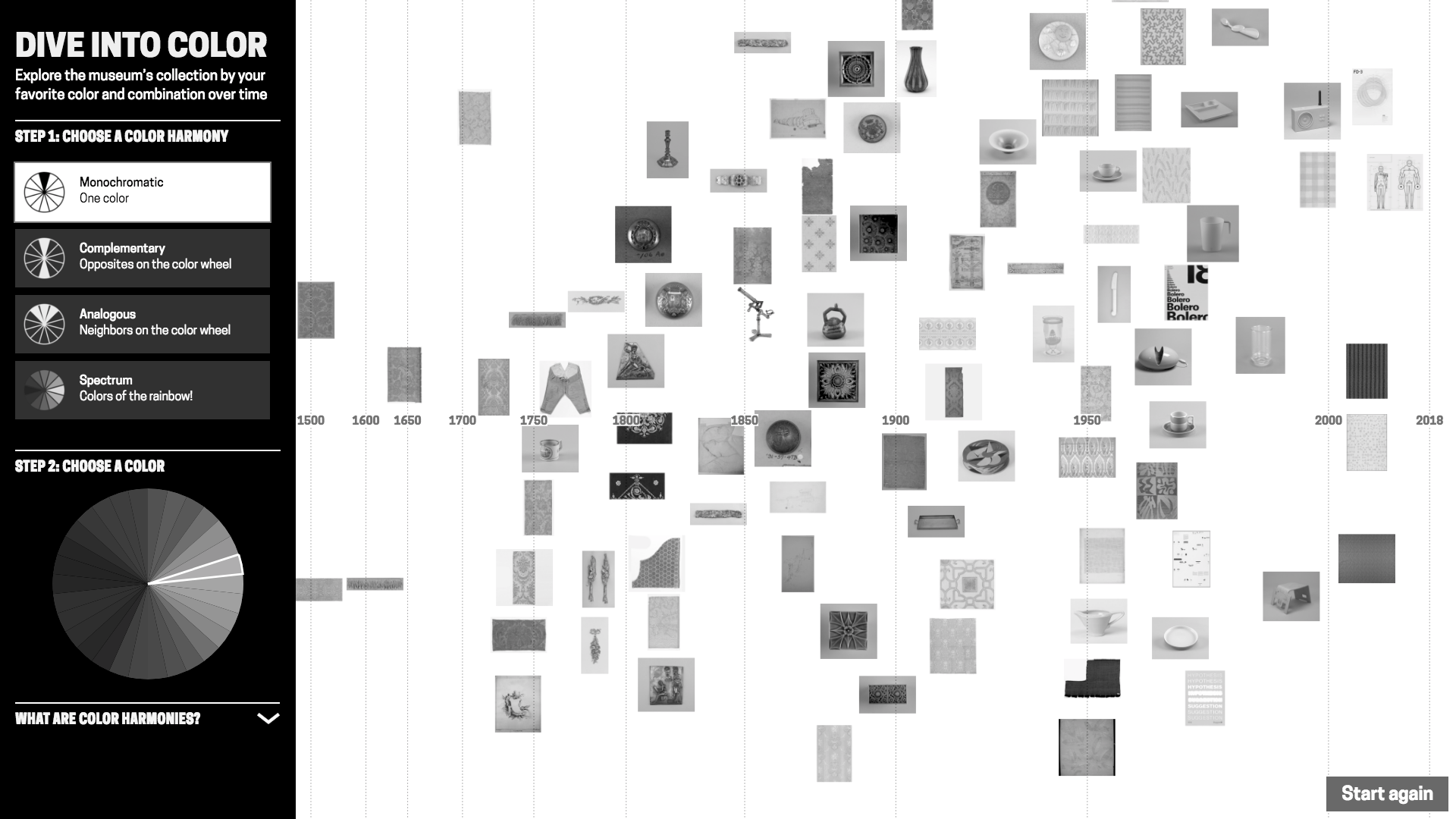

In a project with the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City, I created a new interface design for searching the museum’s collection by colour and colour combinations. (Colours were extracted from the photographs of the collection items algorithmically). Displaying the results on a timeline makes it possible to spot colour innovations and trends.

Olivia Vane. 2018. ‘Dive into Color’ visualisation of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum collection.

This is not just a moment to recreate, but to reinvent. Scholars, researchers, and designers working in the digital humanities have been thinking about and making things around these ideas for years. Now their work is needed more than ever.